Dr. Gregory Eastwood, ’62, Examines End-of-Life Issues in New Book

Related Posts

Connect With Us

February 22, 2019

By Chuck Carlson

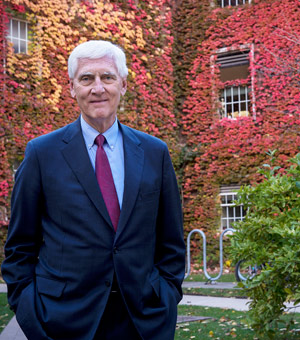

Dr. Gregory Eastwood, ’62, has taken his experience as a medical doctor and ethicist to write a book about end-of life issues.

In many ways, Gregory Eastwood, ‘62, has been preparing to write his first book ever since he knew he wanted to be a doctor.

“When I talk about this to non-medical audiences, I begin by saying every person in this room is an expert on the topic,” he said. “This is not esoteric knowledge; it’s something everyone experiences.”

The subject? Death and the process of dying, a topic that has been explored for years but which continues to mean something different to everyone.

“Everyone has experienced the death of a relative or a friend,” said Eastwood, who for decades as a doctor and an administrator and a bioethicist has seen the process closely and all too frequently.

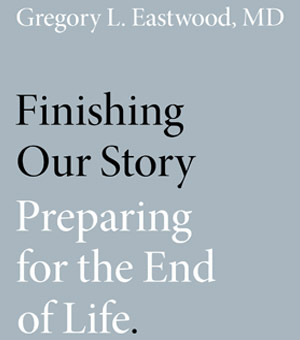

To that end, he has written a book titled Finishing Our Story: Preparing for the End of Life, which is being published by Oxford University Press and will be available in March (though it can already be found on amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com).

His approach is straightforward and, he hopes, will provide information for those who face the end of life as well as those who are left behind.

“It’s about how to deal with it,” Eastwood said. “How do we better understand the end of life and prepare for it? It would be hubris if I said the book answers everything. But I try to address most things that I think are important.”

Indeed, the chapters make that clear with titles such as, “Dying Isn’t What It Used to Be,” “The Good Life,” “Making Our Wishes Known,” and “May I Choose to Kill Myself?”

“The process of dying has changed a great deal,” Eastwood said. “Death is the same. That hasn’t changed. My story is pretty typical of those who write a book. I’ve been thinking about this for a long time because I’ve given talks many times on the end of life.”

Interest in Medicine Took Root at Albion

Eastwood’s interest in the subject developed from his years at Albion College, where he majored in biology. But he was determined to be a doctor and follow in the footsteps of his Sunday school teacher, Gerald Wilson, in Detroit.

“He was in his last year of surgical residency (in the Grace Hospital System in Detroit) and I was very impressed with him,” Eastwood said. “He planted the seed for being a medical doctor. I went on rounds with Dr. Wilson in high school and when I was in college, between my freshman and sophomore year, Dr. Wilson got me a job as an operating room technician. So I scrubbed and was in the operating room and handing instruments to surgeons.”

Dr. Wilson also provided the young Eastwood with medical textbooks and allowed him to dissect the arms and legs of a cadaver.

The cover of Dr. Eastwood’s book, which will be released in March but can be ordered now on amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com.

“I expected him to show up and help me but he never showed up,” Eastwood said. “So I did it myself.”

Once he graduated from Albion, he set his sights on attending the same medical school as his mentor—Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio.

After graduating from medical school, Eastwood trained in internal medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and in gastroenterology at the Boston University Medical Center. He has subsequently held faculty appointments at Harvard Medical School and the University of Massachusetts, where he was director of gastroenterology.

He has also served as dean of the Medical College of Georgia and was president of the State University of New York-Upstate Medical University in Syracuse from 1993-2006. He then returned to Case Western Reserve to serve as interim president and director of the Inamori ethics center for a year before returning to SUNY-Upstate in 2008, where he taught bioethics and served on the University Hospital ethics consultation service before being appointed the school’s interim president from 2013-16.

Since then, he has lectured and taught medical and other health professional students as well as served as an ethics consultant in the Upstate Medical University Hospital in Syracuse. Finally, during a six-month sabbatical in 2016 from SUNY-Upstate, he wrote the book.

“I just did it,” he said. “As I was writing the book, I realized I had internalized a lot of these experiences. I relied most on experiences from 2008 as a bioethics consultant and I got a real understanding of what the issues were. It was that experience that made me much more aware of the issues I talk about in the book—how dying has changed from a relatively straightforward process to all the gadgetry and prolongation and expense. It’s almost a perversion from the normal process of dying.”

He knows his book won’t answer every question about end-of-life issues, but he hopes it provides a chance to make the process a little easier to understand.

“I think it is important to be aware of the process of dying and how it plays out in contemporary America,” he said.

Sharing His Knowledge

Still working part-time and living in Syracuse with his wife of 54 years, Lynn Marshall Eastwood, ‘64, and who he met in a Russian language class at Albion (“It took me a month or two to ask her out,” he said), Eastwood is now using his medical education and training to consult with Albion’s Lisa and James Wilson Institute for Medicine, which will introduce the first courses of a revamped pre-medical curriculum this fall.

“I’ve been in medical education literally since I started medical school,” Eastwood said. “And it’s been interesting to see that as medical curricula have changed and evolved over the years, pre-medical curricula have not changed much. [The Wilson Institute] is a good idea. It has the potential to be more effective in preparing people for medical school. There’s the traditional notion that you have to learn a lot of science, but you need more experience at the undergraduate level of living, of non-medical topics like philosophy, economics, languages and how medicine works. That’s what Albion is trying to do.”

Brad Rabquer, associate professor of biology and Wilson Institute director, said Eastwood brings a wealth of knowledge and that his advice will be vital.

“Dr. Eastwood has been a leader in medical education for a long time, and his research shifted toward medical-ethics experience as it pertains to training medical students and residents,” Rabquer said. “It’s a perfect fit for what we’re doing. Certainly he’s someone I would look to for advice as we look to incorporate aspects of ethics into our curriculum. From his perspective as a leader in the field, it’s nice to recognize we’re on the right path.”

To that end, Eastwood is scheduled to visit Albion next fall, on October 25, to speak with faculty, staff and students and offer some insights culled from five decades in the medical field.

“I just hope I can offer something,” Eastwood said.