Dr. Carl Hart, Common Reading Experience Author, Visits Campus

Related Posts

Connect With Us

Columbia professor discusses his acclaimed 2013 memoir in Goodrich Chapel

September 23, 2016

By Jake Weber

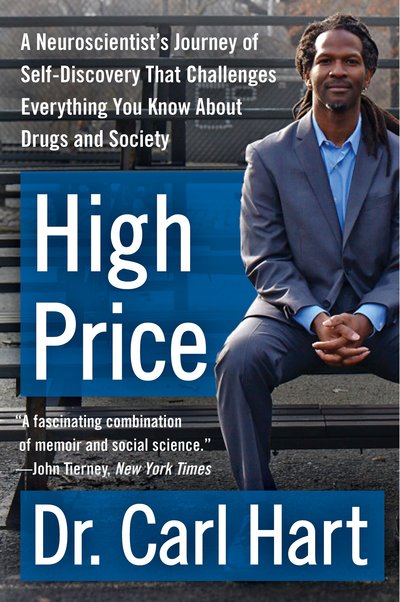

Hart’s High Price won the 2014 PEN/E. O. Wilson Literary Science Writing Award.

Neuroscientist Dr. Carl Hart brought hard science—and sometimes harder conclusions—to an attentive audience September 22 in Goodrich Chapel for the 2016 Richard M. Smith Common Reading Experience lecture. The first tenured African-American in the sciences at Columbia University, Hart is the author of High Price: A Neuroscientist’s Journey of Self-Discovery that Challenges Everything You Know About Drugs and Society.

“I thought if I could cure drug addiction, I could cure all the problems my community faced,” said Hart, a Miami native, explaining his career path. His research, however, led him to understand his first point: drugs are not the problem.

“Most people who use most of the drugs we’re concerned about, don’t have a problem. They go to work, they pay their bills, and sometimes they become president of the United States,” Hart said, noting that the last three U.S. presidents are known to have admitted to illegal drug use.

Hart debunked a famous study that indicated rats, taught to press a lever and receive drugs, would die of drug consumption. “What this study doesn’t tell you is that these laboratory animals had access to nothing but that lever,” Hart said. “When laboratory animals have alternatives, they engage in other behaviors more than they take the drugs.”

In his own lab, Hart discovered that even crack cocaine addicts would forego offers of drugs when a desirable aternative (e.g., money) was offered. “These people were engaged in high-level congnitive functioning, which we said they couldn’t do,” he noted. Even addicts “can and do behave rationally. Increased alternatives decrease drug use.”

Hart acknowledged that the roots of addiction are varied and complex, but “when we focus on drugs as the root of addiction, we miss the point.”

Hart also asserted that “we, in science, have participated in exaggerating the harmful effects of drugs.” Acknowledging the controversial nature of the statement, he used the example of Adderall and methamphetamine, drugs whose chemical difference is irrelevant in its effect on humans.

He cited a second example in heroin. “Seventy-five percent of heroin overdoses are from mixing heroin with something like alcohol,” Hart said. “The public health education messge should be not that we are experiencing some heroin epidemic,” he said. “The major message should be, ‘Don’t combine it with another sedative’ if we want to keep people safe.”

Hart postulated that an “addiction industry” is inadvertently making the problem worse. Governments, law enforcement agencies, treatment providers, and other instiutions benefit from expenditures to fight drugs and addiction. “We don’t have to deal with unemployment and poor education when we say, ‘We’re going to rid that community of heroin,'” he said.

Hart was most critical of the high price paid by African Americans and Hispanic Americans in the war on drugs. Although whites and nonwhites use drugs in the same percentages, nonwhite users have been punished more, and more harshly, in the U.S. This is institutional racism, he said.

“All of us should be outraged that this sort of unfair treatment is happening in our society, with its great democratic ideals. We must change the image we have of the drug user,” Hart urged, saying that drug users need to “come out of the closet.”

Following his presentation, Dr. Carl Hart (on stage) listens to a question from audience member Dr. James Curtis, ’44.

Conversely, he encouraged more focus on improving poor communities, thus decreasing the use of drugs among already marginalized communities. He also advocated for the legalization of drug use. Finally, he said, “We have to engage the public. In these spaces of academe, we become insular and don’t talk to those outside of these spaces. We need to help people use evidence to guide their positions.

“The formula I give you today will not enhance your popularity,” he concluded. “People don’t like to hear we’ve been told lies about drugs. You may not be popular, but history will judge you fairly.”

The Common Reading Experience is a part of the College’s First-Year Experience in which all of Albion’s first-year students read a shared text that serves both to connect students to one another and to help them make the important shift from high school to college. Consistent with the College’s commitment to learning in and out of the classroom, the CRE involves both formal discussions in First-Year Seminars and informal discussions in the residence halls and around campus. Like the liberal arts, the dynamic and thoughtful CRE programming supports, challenges, expands, and enriches the students understanding of the core text and its ideas by helping them approach it from a number of different disciplinary perspectives.