‘Lofty idealism’ Drives Evan Rieth, ’19, and His Desire to Be a Farmer

Related Posts

Connect With Us

December 21, 2018

By Chuck Carlson

He was known, at least for a while, as the “Mustached Milkman of Albion College.”

That’s because, even before the dawn proverbially cracked, Evan Rieth, ’19, would be milking cows at the Weathered Silos Farm in nearby Hanover and deliver raw milk—a half gallon to English professor Nels Christensen and a gallon to several students on campus as well as delivering it weekly to the Marshall Farmers’ Market.

“And I get a gallon every week for things like yogurt and mozzarella,” Rieth said. “I drink raw milk and I also think pasteurized milk is a good thing.”

Evan Rieth, ’19, worked on Granor Farm near his home in Three Oaks, first as an intern and then lead farm hand, as he continues to gain experience and knowledge about farming.

Then he smiles.

“Cows can turn grass into milk,” he said. “How amazing is that?”

These days, the impressive mustache is gone, done in by a recent lost bet in which, as a member of the College’s equestrian hunt seat team, he wagered the continued existence of his facial hair that he would win his final competition of the season. He didn’t.

“I finished second,” he said.

But for Evan Rieth, it’s time to move on to the things that matter most and for which Albion has prepared him.

“I like producing food for other people,” he said.

And the environmental studies and English major believes he can do just that, even though he knows just how complex that goal is.

“I’m also a bit of a romantic,” he said. “I like to believe in a certain amount of lofty idealism.”

It’s not a misplaced idealism either. He grew up on a 60-acre farm in Three Oaks, Mich., and farming has always been a major part of his life.

That’s why he’s milked cows in the dark. That’s why last summer he worked on a 1,200-acre farm in Essex, N.Y., that featured a program known as Community-Supported Agriculture, where local people would pay to choose the type of produce and meat they wanted. That’s also why he spent the fall semester of his junior year in a food sustainability studies program in Italy and why he worked two summers at an organic farm near his home.

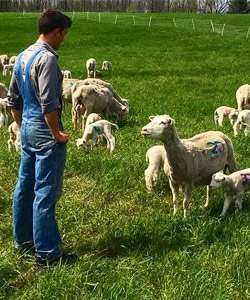

Rieth visits some of his friends last summer at a farm in Essex, N.Y. “Farming is what gets my mind working the fastest,” he said.

“He’s hungry to do things and to know things,” said Christensen, who has taught Rieth in four classes over the years, including one titled Redneck Environmentalism. “Even this year, he’s asking me what classes he should be taking to make him a better student. He said he wants to get the most out of a liberal arts education.”

And it’s why he plans to take all he’s learned, and all he still has to learn, and become what he believes he was always destined to do and be—a farmer.

“Farming is the most difficult thing I’ve ever done,” he said. “It’s an extremely sensory experience and it’s what gets my mind working the fastest.”

Rieth came to Albion already interested in farming and after a discussion with Professor Tim Lincoln, who was director of the College’s Center for Sustainability and the Environment, Rieth knew that was still the direction he needed to go.

“That checked off a lot of the boxes I was looking for,” he said. “I knew it would challenge me when I came here. And it definitely has challenged me. I came to Albion thinking farming was my passion but I needed a different way to manage it.”

So he’s taken a variety of courses that he knew he’d need if he wanted to be a successful farmer in 21st-century America.

So not only has he taken courses to fulfill his majors, he’s taken geology and sustainability classes and a biology course about vascular plants.

“There’s nothing better if you want to be a farmer than to go to a liberal arts school,” he said. “I can better react to the challenges presented to me.”

And there will be challenges. From weather to crop prices to disease to a fluctuating economy and more tribulations Rieth probably hasn’t even imagined, the task of feeding people will not be easy.

In fact, his senior thesis is titled “Reimagining Agrarian Society for the 21st Century,” in which Christensen is his advisor.

To help him learn what farmers in the future can and must do, he is also traveling to Vermont and upstate New York, where young farmers are doing exactly what Rieth wants to do.

“There’s a high concentration of young farmers and they’re making it work out there,” he said. “It’s an opportunity to learn what it’s really like to run a farm business. I know how to milk cows and grow vegetables but I don’t know how to file taxes.”

Christensen said it’s that desire to learn what he doesn’t know that sets Rieth apart.

“And he’s fine with failure,” he said. “He gets excited about being told he doesn’t do something well because that gives him the chance to learn.”

Asked if Rieth will succeed in his goal as a farmer, Christensen smiles. “He’s going to succeed in whatever he decides to do,” he said.

Rieth knows it won’t be easy providing food in a challenging enviornment. So he prepares for an uncertain future with no guarantees of anything. And he wouldn’t have it any other way.

“We know what we should do; now we should do it,” he said. “I know I’ll get a lot of things wrong but we need to start doing it. And I won’t be satisfied until I start doing it.”